Broken Homes

A keynote address by Sue Hill

This paper focuses on the complexity of notions of ‘home’, with special reference to the work I have been doing in conflict areas, through WildWorks and the Eden Project, with people who have experienced what happens when more than one tribe thinks of a place as their home. The word ‘home’ conjures cosy images of safety, comfort, warmth. But ‘home’ can also imply ‘homeland’ and ‘territory’. I explore what ‘home’ means for the communities we have worked with in Kosovo, Cyprus, and the West Bank, and the significance of collective memory of place in culture and identity. Finally I examine the role of the artist making work in and for these post-conflict areas with the people who live there, describing pitfalls and sensitivities and proposing a set of guiding values and principles.

My home is Cornwall, and I think that has been a powerful foundation for my practice; the connection to home and the way in which every part of your intelligence – all your intelligences; your emotional intelligence, sensual intelligence and cognitive intelligence are all bound up in place, in your territory. So much of my work (even when I’m not in Cornwall, maybe especially when I’m not in Cornwall) has been to do with what connects people to place.

These are just a few foundation examples of recent work, not in conflict zones, which have been intimately tied in to peoples’ connection to landscape and place…

We made ‘Souterrain’, the story of Orpheus in seven places in the UK and France. It is a tale of grief and our reluctance to confront loss. We took audiences, with Orpheus, on a journey into the underworld. And in each place we made it, we created the underworld of that place. Stanmer, near Brighton, is a village that is dying. It is owned by Brighton City Council. Every time a tenant leaves or dies the council don’t re-let the house. So the dairy farm no longer has a tenant, and there are five or six more houses in the village that are empty. The village knows it’s dying. We worked with the people of this village, and they described their connection to it, and what they love about their lives there. With them we made installations in their gardens expressing their sense of connection. One woman made a piece using her own, her children’s and her grandchildren’s baby clothes, a skein of knitwear spanning generations. Another made an installation that hung on one of the empty houses, a tribute to the people who had lived there.

This is John Gapper – a pastoral eco-warrior. He describes growing up in the valley, a place full of bees and butterflies, insects and wildflowers, many of which have vanished because of contemporary agricultural practice. He collects seeds of local plants, grows them in pots in his back garden, then ventures out at night to plant them in the bland green pastures. You’ll be walking through the fields and see a bank of cowslips, and you’ll know – ‘John has been here’. He had an ancient landrover, which hadn’t moved for 11 years. With him we turfed it and turned it into a shrine for the valley he remembered. There were peepholes in the side through which you could peer and see insects and butterflies, native plants and flowers. On the second night of the show the audience, Orpheus and his soldiers came up the street looking for Eurydice and there, on top of the landrover, was John Gapper, watering his beloved plants. He became a regular part of the show after that night.

In Port Talbot, we made The Passion, with Michael Sheen. Again, the starting point was ‘what does this place mean to you?’ The starting point, working with this community, was to mine their memories and their connections to place. Our story proposed that Pilate and his occupying army were preparing to clear the people from the town. Participants in workshops were invited to bring a photograph of the place they would miss most if they were exiled from their homes. Putting the things that people love and value most under imagined threat provoked inspirational storytelling and powerful emotional connection to the project.

This is the making of Christ’s shroud, made up of work by people from all over Port Talbot. Clubs, primary schools, sports groups, the W.I. and the old people’s homes on the seafront made embroidered emblems of their town, and what it means to them. So many squares arrived that we made two shrouds that are now proudly hung in the town on high days and holidays.

This is Michael on the cross. The images projected on the water screen behind him, are people’s photographs and home movies, memories of Port Talbot made visible. His speech at the end from the cross is about him remembering, but it’s actually everyone else’s memory, lists of characters, places, events. So when he calls the name of the particular place where everyone used to lose their virginity – ‘Number 9 Tump’ – a great shout rises from the crowd because they recognise it, and they understand it, because it’s theirs too. Port Talbot has had many challenges; the polluting impact of industry, the social and economic effects of the loss of that industry, the experience of living underneath the motorway. But in spite of these, or maybe because of them, Port Talbot is one of the most vibrant and cohesive communities I’ve ever worked in.

Lyn Gardner said, in The Guardian ‘Hewn with tenderness from the memories of locals, and largely performed by them, this production was like watching a town discovering its voice through a shared act of creation.

This is ‘Count Your Blessings’, a project we made in North Cornwall, looking at reintroducing the large blue butterfly, which had become very rare due to agricultural practice. We worked with the farming community around Morwenstow, and turned their experiences and memories into small shrines and memory boxes. Throughout the Christmas period these were placed around the village, in the pub, in the shop, in the school. This installation was inspired by the stories they told of when the horses went. Their lives were so intimately bound up with horses. They embraced the arrival of tractor with such joy, but hadn’t counted on what happened to their sense of themselves when the horses left their lives – someone described it as losing a member of the family, because the horse was so much a part of their life and their culture.

Sometimes we remove the idea of ‘home’. This is research we did for ‘The Beautiful Journey’, where we tried to imagine a future. To help people visualize a future we invited people to imagine that they have to leave their home, to which they may never return, and to choose seven things without which life would be unbearable. Over a period of 18 months we invited people to bring us their seven things, and to tell us the stories of their choices. Their choices are very revealing of the kind of nomad future they imagined for themselves. Some people chose things that were practical, others chose heart and spiritual things – and almost everybody brought something that reminded them of their home and family. This is a writer’s selection, so she has her notebook and pencils. She adores her dogs, so the collar speaks of home for her. The charms from Cuba speak to her of her Spanish roots.

These are the seven things of a practical archaeologist; she solves archaeological and historical conundrums by practically making things. Each time, we asked at the end of their story telling ‘if you could only take one thing, what would you take?’ This woman chose string. We asked ‘Why not an axe or a knife, why string?’ She said ‘I know how long it takes to make string, you have to grow it for months, you have to ret it, you have to work it. It can take you a year or more, 18 months, to make string. And with string I can make my home, secure my animals, tie things in a pack so I can travel’. Home is a piece of string.

These are the home-patch projects, where people are describing the intimacy of their connection with home, and the security of it, even when it’s taken away.

Now I’m going to describe three experiences where I’ve worked in places where home is not safe.

Cyprus

‘A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings’ lasted three years and was a Kneehigh collaboration between artists in Malta, Cyprus and Cornwall – performances being created in the three countries in successive years. It was inspired by the Gabriel Garcia Marquez story of the same name. It’s a very simple story – one day in a little village miles from anywhere, a poor but happy village, a very old man with enormous wings arrives, and the villagers don’t know what he is. They think he might be a demon or a big chicken, or possibly an angel. So they send the postman off to the Pope to find out, word spreads, pilgrims arrive, bringing money to the village. You can imagine the rest. In each place we played this story it accepted different meanings; the meanings in Cyprus concerned what fractures a community.

This is the edge of the green line; we’re standing in Greek Cyprus and the houses you can see in the distance are on the other side of no man’s land, in Turkish Cyprus. Nicosia is one of the last divided cities, the two ethnicities separated by a few hundred metres of waste ground and barbed wire, uninhabited since 1974, policed by the UN. If and when the wire comes down, they’re talking about making it into a nature reserve, because it now is wild and overgrown. But you can imagine what it’s like living in a city that is divided in this way. There are UN border guards at regular intervals with machine guns. We had to negotiate with the UN to fly our Winged Man; they were worried he would be picked off by sniper fire.

We were able to get permission for Turkish-Cypriot artists to join us from across the border, they came through passport control every day to work with us. The border had only recently been opened and people had started to come through from one side to the other.

The young artists we were working with had all been born after partition, but some memories are longer than lives. They had never encountered the enemy, but their families’ stories of violence and atrocity are scorched into their consciousness. The way in which memories are communicated and stories are told, perpetuate the fear and anxiety about the power of the enemy.

Imagine what’s it’s like on the first day of rehearsals when a group of Greek Cypriot artists is meeting a group of Turkish Cypriot artists. These young people have never met the ‘enemy’ before, and the tension is palpable. In the first week of rehearsal Bill asked one the Turkish Cypriot artists to teach a traditional dance from his own village. One of the Greek Cypriot girls stopped dancing; she sat down and she was pouring with tears. Bill said ‘What’s happening here, are you ill? What’s the matter?’ She said ‘This is my dance. This is the dance we dance in my village’. This was a moment of epiphany for us all – the company became a company of Cypriot people rather than ethnically Turkish or ethnically Greek. It was also a lovely secret moment in the eventual show, that these two, the Greek Cypriot girl and the Turkish Cypriot boy, danced their dance together.

There’s a story that came to us by one of the Greek Cypriot artists; his father, at the time of partition, had been living in the North, in Kyrenia, and had had to leave his farm very suddenly to flee to safety in the South in Larnaca. Greek Cypriots living in the North and Turkish Cypriots living in the South fled to find new homes and to make new lives. Over the course of the intervening years the vacated properties were taken over, some even sold as holiday homes or occupied by new families, many from the Turkish mainland. When the border opened again not many Greeks went North, but after 30 years he wanted to see his farm, so he went. His groves of olive and lemon were still there, unharvested and untended but surviving. He knocked at the farm house door and a little, old, Anatolian lady answered. He spoke a little Turkish so they were able to have a conversation and she made him some mint tea and he sat down in his old kitchen, and it was fine. Then the time came to go. He had noticed that in his kitchen, or what had been his kitchen, there were wedding photographs – his wedding photographs – still on the wall. There was a beautiful picture of his mother, and his mother had since died. He had no pictures of his mother as a younger woman so he asked his host ‘Please may I take this photograph with me?’ She said ‘Yes of course, but you will pay me $50’. This story speaks so powerfully about the situation in Cyprus – although I guess it’s changing now with the economic crisis in Greece – but in recent years the Turkish North has been terribly poor, and the Greek South has been incredibly rich, so there’s been a tension in the economic status of the two territories as well as the history and culture.

Kosovo

My work in Kosovo has come through the Eden Project, I’ve been working in Kosovo since 2004. It happened because of a garden. In the late 90s there was a period of ethnic cleansing where the Serbs were allowing militia to penetrate Kosovo to kill and execute predominately Kosovo men, and to blow the roofs off the houses to make them uninhabitable.

This is an image of revenge, the Kosovan Liberation Army did this to a Serb church. It’s in Podujeve, a town inhabited mainly by ethnic Albanian Muslims in the North of the country, close to the border with Serbia. It is near the gold, zinc and coal fields of Mitrovica and is among the most intensely fought over territories in Kosovo.

Outside the Parliament Office in Pristina there is a fence, and on the fence there are many images of the missing. There are still many untracked and unidentified bodies. The last time I was there they had found another mass grave of 300 behind the apartment where I was staying. When I first arrived I had a security induction from the UN – they showed the mine and cluster bomb map, and pictures of ordnance so you can recognise a cluster bomblet at your feet. In the UK we can walk across country landscapes without fear, but in Kosovo you stay on the road because it’s dangerous to do otherwise. Imagine what that does to people, the lack of connection to the natural world and for children to not be able to go and play in fields and woods.

This is part of what is to become the Peace Park in Kosovo. The Serbs used to position a sniper in this grain silo, and from there could survey and control the whole town. So this is a very frightening place. In March 1999 the people of Podujeve heard that they were being targeted by a Serb militia, the Scorpions. They did what a lot of other towns had done; the men left the town and hid in the hills. The town was full of women and children, and old people who couldn’t leave. The Serbs managed to corral nineteen women and children into a beautiful courtyard garden and machine-gunned them. Seven adults and seven children died, five children survived.

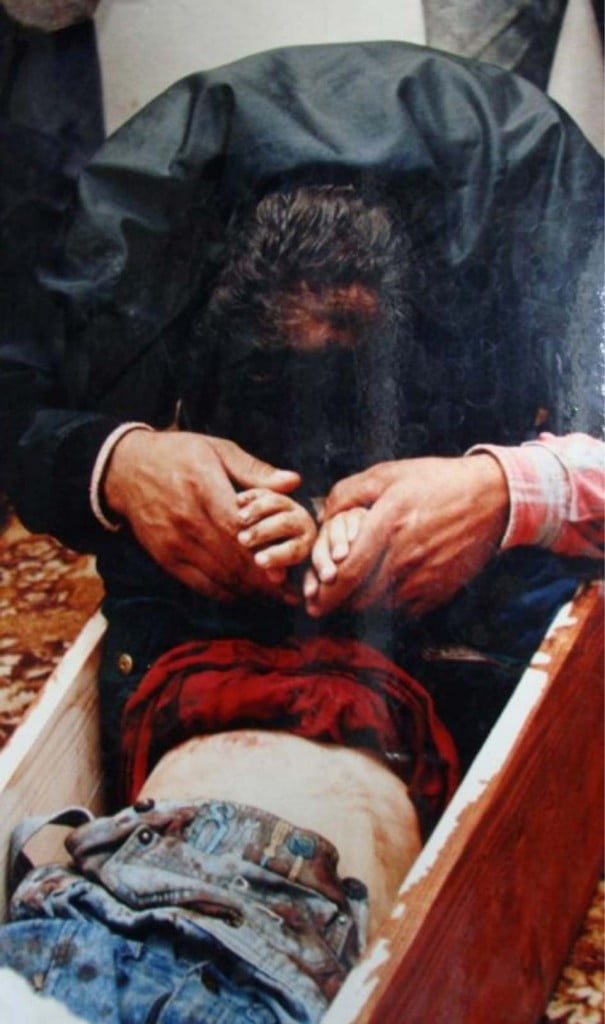

This charred and water-damaged image was retrieved from the ruins of one of the families’ houses. It shows one of the survivors, Saranda, and her best friend, Nora, who didn’t survive. They were cousins and best friends – they even wore the same clothes. Saranda was the eldest of the children who survived, she was 14 at the time of the atrocity. The children were evacuated as medical refugees to Manchester; they had gunshot wounds and were traumatized by having lost their families. Communities in Manchester were, within weeks, sending container loads of aid to Albania, where many refugees had gone. They took these children to their bosom and nurtured them, gave support to their surviving families and set up a charity called Manchester Aid to Kosovo. When the leader of the Scorpions, Sasa Cvetan, was caught Saranda was asked to go and give evidence to the war crimes trial in Serbia. Manchester Aid to Kosovo supported her and went with her to Belgrade; at the age of 15 she gave evidence, the youngest person ever to give evidence at a war crimes trial. When the children returned to health and went home to see their other family and friends in Kosovo, they decided that they wanted to make a peace park in commemoration of those they had lost, but also as an act of healing for their community. They loved the public parks and green spaces that they had experienced in Manchester – there isn’t anything like this in Kosovo. Manchester Aid to Kosovo approached the Eden Project and said ‘Please will you help us?’ They had been given a piece of land by the municipality right next to that hideous tower, a swampy field and a patch of woodland. It was initially covered in litter and sewage, and the area had to be cleared of mines. With the people of the town we started to design what is now called the Manchester Peace Park.

This is part of our crew – we didn’t just have children to work with us – but 80% of the population of Kosovo is under 30 years old, a lot of the older people died, so young people and children have been very significant contributors to the peace park. We have also been working in collaboration with nine young artists, a group called Visioni i Paqes – ‘vision of peace’ – arts students at the university in Pristina, studying sculpture and fine art. They have dedicated themselves and their art to healing their country. They say ‘Art hasn’t got a country, language or religion and has no boundaries’. I’ve been working with them since 2004, they’ve been helping to design the peace park and doing projects with people in Podujeve and beyond.

When we first arrived and went to see their work at the university in Pristina, their art practice was very traditional; to sit down and draw a Greek bust or to model their own heads in clay. They had had no exposure to any kind of contemporary art practice but had curiously become stuck in a particular period of early 20th century art study. So that was a really interesting and challenging question for us; what is your responsibility? Do you teach them? No, that would risk simply replacing one set of rules and approaches with another, a kind of art colonialism. But we did expose them to a lot of new ideas. We managed to get visas to bring most of them to the UK, to undertake residencies, work in foundries and work alongside British curators. Their work has grown immeasurably in scope, ambition and achievement. It speaks truthfully of their experiences growing up in conflict and of trying to make sense of the new Kosovo.

There is an art gallery is Pristina, above the museum, and when I first visited this is what it was showing. These are the least horrific photographs from that gallery, and it makes you question what art you make in the face of memories like this. What is your role? What do you do? It makes me feel very helpless, to find a way of responding to it. Ultimately I felt that facilitating the Kosovars’ work was the most powerful thing we could do.

So we worked on the Peace Park together and that became the most compelling and absorbing art project. The Visioni artists worked with Cornish artist Lucy Birbeck and with children in Podujeve to come up with images that were powerful for them in order to make flags that can be flown as a symbol of joy on celebration days.

This is the image they chose – Orpheus and his lyre, which might seem strange, but there’s a wonderful mosaic of Orpheus that was taken by the Serbs from a site just South of Podujeve. It is now held in a museum in Belgrade but the Kosovars say it’s theirs. It’s a very powerful and resonant image of ancient Illyria which existed where Kosovo is now.

And yes, the Kosovars we have been working with very much want to make a version of ‘Souterrain’ for Podujeve.

This is Saranda, the young woman who went to Belgrade to give evidence at the war crimes trial; she is now living in the UK, having just finished an MA at Manchester University in fine art. On the 10th anniversary of the atrocity we held a dedication ceremony. Flags were flown and we all gathered together to celebrate a new start for the people of Podujeve. I finally exhibited the installation I had made using the children’s artwork imagining a peace park, inside some of the wreckage from the Serb church, a kind of peepshow into the future.

The West Bank

WildWorks was invited to take part in PalFest, the Palestinian Literature Festival, which is directed and curated by Ahdaf Soueif, the Egyptian writer who wrote The Map of Love, and who wrote dispatches from the front line in Tahrir Square during the Arab Spring. PalFest is a travelling festival. The Palestinian people of the West Bank are not free to travel in Israeli occupied territory, so the artists and the festival must go to them, presenting work and holding workshops in Jenin, Ramallah, Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Nablus, Hebron and, some years, Gaza. We ran workshops in the universities and at the Freedom Theatre in Jenin.

The conflict between these two tribes is so present, you are constantly aware of it. You see the separation wall erected by the Israelis everywhere you go.

This is such a profoundly contested land. This is Abraham’s Tomb in Hebron. It’s in the Tomb of the Patriarchs which contains Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Jacob and Rebecca, all of which are significant figures in Islam and Judaism. This view is from the Islamic side, that glass screen is bullet proof and what you can just see through the window is an Israeli Jew making their religious observance.

This is a Palestinian house near Bethlehem. The separation wall has come to the house, gone around the house, and continues on the other side. What you can’t see in this image is that on the other side of the wall is the olive grove that belongs to the house. The Palestinian who lives in this house can no longer tend that olive grove. Current law states that if you don’t tend your land for 3 years it defaults to the state. The separation barrier is there because the Israelis say that the wall defends their people and their communities against the violence that the Palestinians perpetrate on them.

This is occupied Hebron. The city is Palestinian but Israeli soldiers are ever present.

This is the souk, the old market in Hebron. In the next picture is an Israeli flag, because there is an Israeli settler living above the souk . It’s netted for the protection of those below because they throw material down into the souk.

Here’s a selection of the kind of thing you might get – a child’s doll is the least toxic thing being thrown – rubbish, decomposing food, used nappies.

This fortified terrace is part of a settler’s house. The issue of land stops being a personal, domestic one and becomes a political, state-driven policy. These settlers are not necessarily Israeli – there is a programme which brings Jewish people from the US to tenant settler’s farms and houses in the West Bank for 6 months at a time, to keep them occupied. In the same way, in Northern Cyprus the Turkish government brought in Anatolian farmers from mainland Turkey to occupy the land – it’s primarily a state government issue, not a personal issue, although it becomes an intensely personal one.

This is one of the formerly bustling market streets in Hebron, now derelict and closed because of the separation barrier. You cannot walk there if you’re Palestinian. PalFest artists hail from all over the world including people from Sweden, Egypt, Britain, USA, France and Spain. Henning Mankel, the Swedish thriller writer was in our group, Susannah Clapp, the Observer journalist, writers Adam Foulds and Geoff Dyer, American photographer Jillian Edelstein, Palestinian American poet Remi Kanazi and many others. We walked here with some Palestinians who had not stood on this street for years. As we started to walk the street a soldier shouted ‘Stop! Where are you from?’ Henning replied ‘We are from the world’. It was incontrovertible, and he had to let us pass, although he knew there were Palestinians in our midst. There is precious liberty in being an artist from a foreign land.

This is the checkpoint at Qalandiyah which is the major check point between Ramallah and Jerusalem. There is no freedom of passage in the West Bank, if you are Palestinian you cannot go from Ramallah to Jerusalem, unless you have a permit. We traversed this checkpoint a number of times, it was a truly dehumanising experience. We were penned and treated like cattle and barked at in Hebrew. But even here there was humanity. We were walking through the checkpoint late one night and queueing alongside us was an elderly Palestinian man carrying a huge burden. As he went through he looked at us and made a mooing sound and we laughed, and he laughed – as if to say that you can do this to me but I’m still human. In fact the only people who seemed to have had their humanity removed by this process were the young Israeli soldiers behind the bullet-proof glass. I had an almost overwhelming impulse to sing in the face of this. I wasn’t brave enough…

Humour is the response of a lot of artists to the separation wall; it is covered with extraordinary imagery.

This is one of Banksy’s pieces on the wall.

J.R., a French artist, has done sensational work all over the world, I’ve seen his work in Kibera and in the West Bank on the separation wall. This is a project called Face to Face; he took photographs of people – in specific roles e.g. taxi driver. He took a photo of a Jewish taxi driver and a Palestinian taxi driver, printed them at a very large scale and pasted them on both sides of the wall.

They are pulling faces, it’s quirky, the images are very compelling. People would watch him and say ‘What’s happening?’ He would explain that there’s a Jewish taxi-driver and a Palestine taxi-driver next to each other. They would question why he would think of putting a Jewish person on the Palestine side, and vice versa. He would reply ‘You tell me which is which then?’

In a community centre in Hebron a Palestinian child has drawn a picture of an Israeli mother feeding her baby Palestinian blood. The toxic relationship between these two tribes is perpetuated by dehumanising the enemy and making them into something you are not responsible for. They become non-human and therefore accepted moral principles do not apply. That’s what we have to confront with our art.

Nabil Al Raee, who has taken over the Freedom Theatre in Jenin after the assassination of its founder director Juliano Mer Khamis, says; ‘the third intifada will not be fought with tanks and weapons. It will be fought with plays, with music, with books and magazines’.

WildWorks is embarking on a project with the community of Nablus to create a piece of promenade theatre in the old souk. Research, funded by the British Council commences in the autumn this year.

What I have described is a series of encounters, fragments of narrative, glimpses into unthinkable places. The stories generate more questions than answers. It can be very confusing for an artist to be active in these places because there are so many risks, not just physical risks to safety, although that may also be true, but rather threats to the integrity of your work. There is the sense that you could be colonising this territory in some way with your practice. There is the tendency for us to fly in and busily undertake problem-solving in our efficient North-European way. It’s important not to exoticise people’s pain. The material you’re presented with in conflict zones makes you feel like you’re working at the front line of human existence. These memories are so powerful; the loss of your mother, not knowing where she’s buried, recovering consciousness and finding your brother is dead in your lap, having to hide under a sack in the cellar while the militia ransack your home – these are extreme experiences, but hopefully not ones we will ever know in our own lives. We gaze at soap operas about hospitals and police chases because those are the places in our culture where we can experience those kinds of intense and difficult moral choices. So this material is very powerful for us, but it’s dangerous as well; as outsiders we cannot live their experiences, we cannot really know. If you’re not careful these people and these stories become your territory, temporarily occupied and exploited. And then you leave, to return to comfort, safety and security.

So what can our role be, as artists?

- To bear witness? We can tell stories that would otherwise not be told. ‘The first casualty in war is the truth’. We can try to see and hear clearly and make account of what we believe to be happening.

- To bring the world? Often people can’t travel, communities can become very isolated, so we can bring new influences in, stories and views from the outside world.

- To bring resources? Although we may feel poor, we are wealthy in comparison to places that have experienced the material ravages of conflict.

- To share tools?

- To be an innocent interloper? Sometimes you can ask a question that is un-askable because you are an outsider, but it’s risky too. I have tried (and often failed) not to leap to judgement. There is always appalling behaviour on both sides in a war, often perpetrated with honourable intentions. The young soldier at Qalandiyah believes he is serving his country and keeping his community safe.

- To convene? As in Cyprus, we can make a space where enemies can meet each other, a space where the focus isn’t on the recent conflict but on making an artwork, telling a story, playing music.

- To talk about something else? It can be a relief not to talk about the war, to visualize another way of living, a possible future.

- To re-humanise the enemy? The weight of catastrophic images and stories of atrocity make it almost impossible to see the people on the other side of the wall as human beings. Art, poetry, theatre, music returns us all to ourselves as fellow humans.

- To show things that cannot be described?

- To make new memories?

- To be inspired and informed? It is re-affirming and nourishing to work with people who have experienced the worst things that human beings can do to each other, yet still have spirit. Saranda is one of the most positive, upbeat people I have ever met; she is full of the future.

- To cheer. We can create joy and bring emotional sustenance.

This last image is from Hebron, to remind me that people are not defined by their pain. Walking back from the forbidden street, through the walls of the city, I came upon a man, a boy and his horse. He lifted the boy onto the horse’s back, which jumped, and the boy looked frightened. Then he gained confidence. The man looked proud, the boy looked proud, we watched and applauded, and they smiled. This was sweet moment, which was not defined by struggle; it was beautiful, universal and human.